I recently wrote a review of Christchurch activist Byron C Clark’s authorial debut FEAR: New Zealand’s hostile underworld of extremists (which will be available in a publication outside this blog in a few months), and discovered to some surprise while writing it that I hadn’t written a book review here in some years. Not since pre-covid, as it turns out! It seems fitting, then, to resume reviewing by doing so with a book that’s been sitting on my personal reading list since before I started the blog. Especially one that remains depressingly relevant to this day.

Now, I’m likely a few months too late for a review of Grant Gillon’s Where There’s Smoke… (a part exposé/part first-hand account of the multifaceted scandal & industrial dispute which roiled the service through the 1990s) to be really topical. However, last year’s struggle on the part of the Professional Firefighters Union and the rank ‘n’ file of the service to win more funding for better conditions, modernised equipment, improved staffing, and higher pay is still somewhat fresh in mind. This especially so in the wake of the deadly floods in Auckland and subsequently Cyclone Gabrielle, which highlighted how easily the emergency services in this country can be stretched thin in disaster conditions. I’ve noticed with a certain measure of pride (being from a family enmeshed in the service) the presence of NZPFU members at strike demonstrations held by the Tertiary Education Union and later jointly by the Post-Primary Teachers Association and New Zealand Educational Institute, and I expect to see them at the coming New Zealand Nurses Organisation strike on April 15th. It seems the support of the union movement, particularly from other public sector unions, has spurred a response in turn. It’s a positive development, and one that I don’t take lightly given the precious few hours firefighters have for their families and personal affairs.

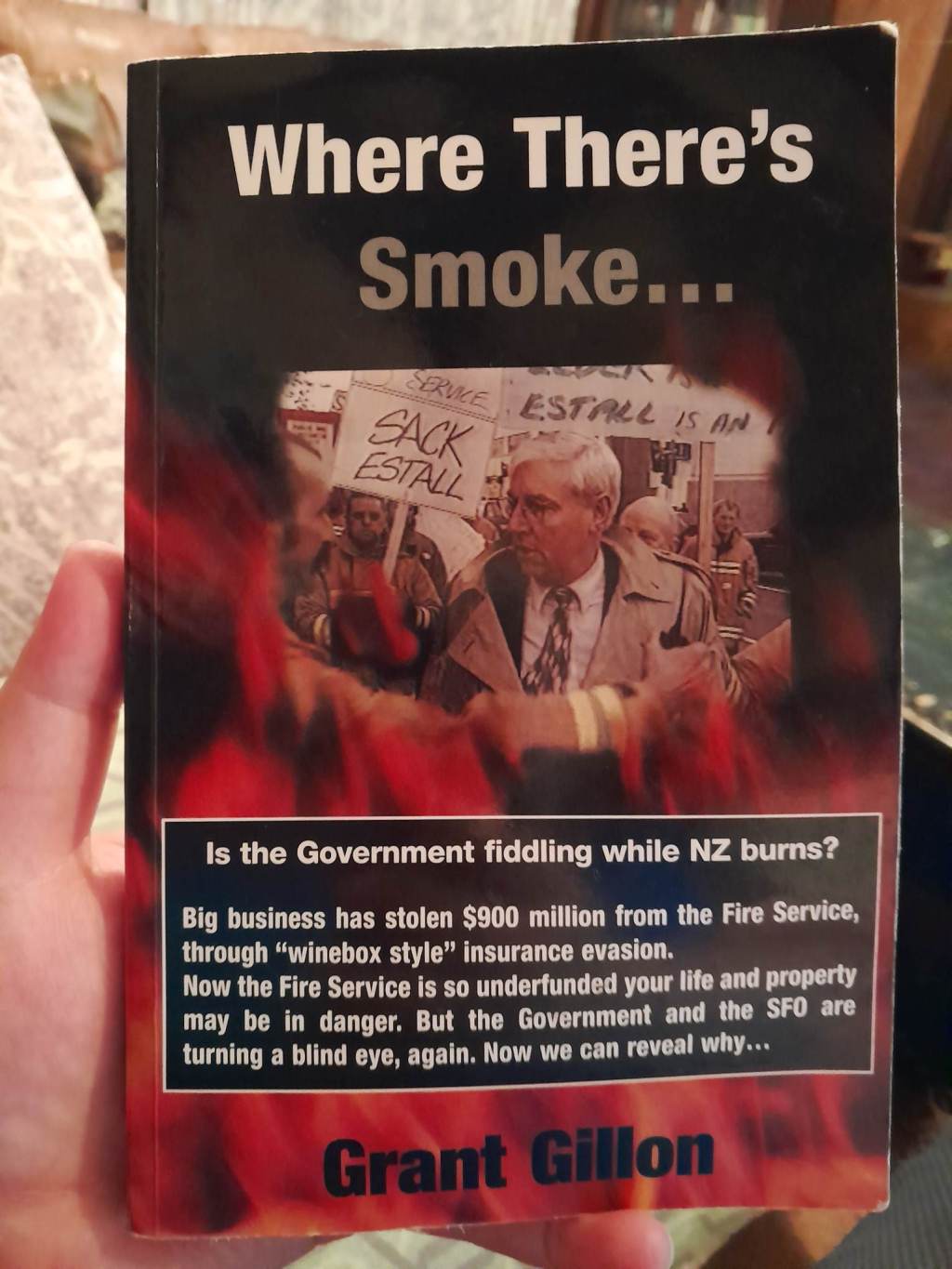

That industrial dispute, with its unprecedented strike by frontline firefighting staff, spurred me on to finally reading Where There’s Smoke…. The scandal in the 1990s has entered into family legend for me, my grandfather being an active firefighter in frontline service at the time, and as such the name Roger Estall was always spoken with venom in my household whenever the state of the service came up. So this has long been on my mind, but it was only last year that I actually picked it up. And I’m glad I did! A lot of the puzzle pieces of what led to the #FireCrisis fell into place as I read it, clarifying just how long and deep the running down of the service really goes. At the core of Where There’s Smoke… are the shady legal loopholes used by insurance companies to help their corporate customers wildly underpay their share of the fire levy, which at the time provided 74% of the overall budget of the service (the remaining 26% being provided by the government). Gillon makes a convincing case that the under-funding of the service, driven principally by these at best unethical insurance schemes, was to the tune of as much as $150 million per year. This on an annual real budget of around $150 to $170 million at the time, leaving some 50% of the funds that were supposed to be available to the fire service largely lining the pockets of companies shirking their share of the fire levy. Throw in that the National government’s choice of Fire Service Commissioner Roger Estall was likely appointed despite not being formally qualified to legally hold the role, definitely had vested interests in the fire insurance industry, was certainly appointed to oversee the radical restructuring of the service, and picked up an unusually large paycheck for his trouble, and you have the making of a serious scandal which would plague the Fourth National Government for years.

Gillon himself would be the driving force in Parliament ensuring that thorn would remain stuck in National’s side until the perennially unpopular Bolger-Shipley government was unceremoniously turfed out at the 1999 election. In fact Gillon, then an Alliance MP as a member of the social credit Democratic Party, was almost the perfect figure to pursue the government over the issue. Himself a veteran of the fire service in good standing, he had written his only other book United to Protect: An Historical Account of the Auckland Fire Brigade, 1848-1985 in 1987, and would go on to gain a master’s thesis and a PhD in public policy in the 2000s after which he would become a senior lecturer in paramedicine and emergency management at Auckland University of Technology. Sufficed to say, Gillon knew the service and was well positioned for any kind of fight over its future.

As a writer, Gillon is if anything incredibly thorough. The book is peppered with lengthy quotes from all manner of legislation, regulation, reports, public statements, correspondence, parliamentary and official documents. It all gives the strong impression of a writer with a purpose, and while it can make the book surprisingly dense for its short length it leaves you in no doubt as to the veracity of his claims. One quickly gains an appreciation for just how much paper Gillon has waded through to gain his extensive knowledge of the issue, both professionally within the service and as a Member of Parliament. With that in mind, this book will repeatedly boil the reader’s blood. Were this (almost) any other industry, this might not rouse quite so much ire. Considered in isolation of the industry in question, the story is a familiar one. Those with the means find ways to avoid taxes and levies, services become rundown, government looks to cut costs, officials loyal to the government are appointed to oversee the restructuring. Same as it ever was. But this public service is unlike almost any other, save for health, in that potential loss of life is an incredibly direct prospect. Much as reduced staff below necessary levels and running down of equipment in a hospital leads very quickly to potential injury or loss of life, understaffing fire stations and failing to maintain high quality equipment causes delays which run the risk of unnecessary harm or damage at any given callout. One does not need much of a talent for abstract thinking to see how one leads to the other.

If I were to levy (no pun intended) a criticism at Where There’s Smoke… it’s the relative absence of the campaign against the proposed restructuring, which warrants some photos and maybe a couple pages in total across the entire book. Those photos and a scant few paragraphs, however, hint at a story entirely untold of a street movement led by a group of workers normally highly averse to the time sink such campaigning entails. Such a story would have been very useful to have recalled in writing during last year’s campaign, but Gillon concerns himself primarily with the intricacies of waging that campaign in Parliament. As such while one element, the ‘official’ campaign waged by politicians and bureaucrats, of the campaign is laid out in great detail (albeit from Gillon’s perspective), the campaign waged by ordinary working people culminating is only touched on in the briefest of terms. How much more interesting things might have been had the long quotes from legislation and official correspondence been punctuated by lively reports from the front lines of the two long marches which wound their way from Auckland and Invercargill respectively to Wellington? Those of us not there can only guess, and so too can we only guess at the lessons to be learned from that now obscure movement slowly retreating into New Zealand’s history.

One thing that Gillon’s considerable focus on the contours of the scandal and its implications for the service does allow for, however, is a number of detours into elements of the story which might not otherwise have been given as much of an airing as they are. An entire chapter is dedicated to what Gillon argues is the botched rollout of the 111 emergency callout system, something he punctuates with very real cases of serious delays and major errors in communication. The chapter is one of the most effective in highlighting how dangerous the restructuring pursued by Fire Services Commissioner Roger Estall, Internal Affairs Minister Jack Elder, and their parliamentary allies really was. In one example appliances from the wrong station are sent to a fatal crash near Tolaga Bay, in another it takes 40 minutes to attend a chimney fire in Invercargill, and in a third three major failures occur in a single weekend in Auckland. The flow on effects of even a relatively minor part of the wider scandal are clear and very dangerous.

At the end of the book, Gillon leaves us where the service itself is left, titling the final chapter “Raking over the ashes”. Where There’s Smoke… remains despairingly relevant, and though the fire service has stored away its placards for now it will only be so long before the same pressures as before leads a government back to mulling over which parts of this vital service can be cut or privatised to meet shortsighted budget expectations. As such, though I reserve some criticism for what’s left unsaid and the overall dry nature of such parliamentary minutia, I find myself recommending this book as necessary to understanding how the fire service reached the point it’s at today. Paired with a more conventional history of the service this is an illuminating look into a public service often taken for granted but highly sensitive to problems with staffing and equipment, with potentially fatal consequences. It further tells the story of a largely forgotten scandal with implications for a great many issues which dominate headlines to this day, disaster preparedness not least among them. Where There’s Smoke… comes recommended by this blog, in the hope that it one day ceases to hold the relevance it retains to this day.

Leave a comment